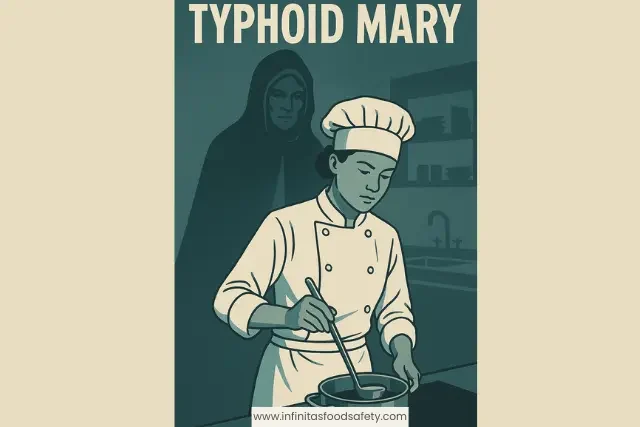

Mary Mallon — better known as Typhoid Mary — is infamous for spreading typhoid as a cook in the early 1900s, without ever being ill herself. Her story isn’t just a grim bit of history: it’s a wake-up call for any food business because any food handler presents a real, invisible risks that can lurk in even the best-run operations.

Let’s look at what Typhoid Mary’s story means for any gaps in your food safety controls — and what to do next.

Table of Contents

Who Was Typhoid Mary?

Mary Mallon was an Irish-born cook who worked in New York in the early 1900s. She was linked to multiple typhoid outbreaks, and tests later confirmed she carried Salmonella Typhi without feeling ill. Public health authorities quarantined her twice — making headlines and fuelling public panic.

How Many People Did Mary Mallon Infect?

Records vary, but most credible sources estimate she was linked to around 50 to 120 infections and at least three confirmed deaths — though some reports put the numbers higher. What matters isn’t the precise number, but the lesson: Mary Mallon was the first clear proof that a healthy-looking person could pass on deadly bacteria through food. That’s why her name still echoes in food safety circles today.

What Is an Asymptomatic Carrier?

An asymptomatic carrier is someone who has a disease-causing microbe in their body, but doesn’t have any symptoms. In Mary’s case, she carried Salmonella Typhi in her gut and shed the bacteria in her faeces, but never felt unwell. In food safety, these “invisible” carriers are the biggest blind spot. They feel fine, but can still contaminate food and surfaces, causing outbreaks without warning.

Today, this risk isn’t just limited to typhoid. Norovirus outbreaks in food business and other infections can also be spread by food handlers who feel well, or who come to work before they’ve fully recovered.

The Invisible Risk in Your Kitchen

Let’s be honest: in most business kitchens, staff still show up sick because they can’t afford to lose pay. The same issues Mary Mallon faced — economic pressure, job insecurity, and a lack of knowledge — are still with us. During the COVID pandemic, we saw the same pattern repeated, with staff going to work while infectious.

Norovirus is the classic modern example.

The lesson? Invisible risks aren’t just about personal hygiene — they’re about the systems and culture you create that supports food safety non-compliance.

Lessons Learned From Typhoid Mary For All Food Businesses

🔹 Handwashing checks:

Make sure you have the basics right — dedicated sinks, always with hot water, liquid soap and disposable paper towels.

Put up clear signage and carry out daily spot checks and record these — it shows you’re serious about food safety. (This is included as an opening compliance check in the Safer Food Better Business Pack.)

🔹 Non-punitive sick policy:

Remove barriers: Don’t punish staff for reporting illness — make it easy and make it normal.

Have written, clear rules for illness reporting.

If possible, offer sick leave. At the very least, make it safe for staff to say they’re unwell.

🔹 Exclude symptomatic workers:

It’s a legal requirement to keep anyone with vomiting, diarrhoea or other symptoms off work.

Only let them return to work after they’re properly cleared. The rule is 48 hours symptom free.

🔹 Vaccination (where relevant):

Encourage staff to get vaccinated before travelling to countries where typhoid is still common, especially if you use agency or seasonal workers.

🔹 Task restrictions after illness:

Anyone recovering from typhoid, norovirus, or similar must avoid food handling until medically cleared by their GP.

🔹 Regular, bite-sized training:

Run monthly five-minute refreshers on faecal-oral transmission and proper hand hygiene technique.

Spot the invisible: Train staff that you can look and feel well but still carry harmful germs that can be transmitted in food to customers.

🔹 Make facilities work for people:

If sinks are hard to reach, soap runs out, or there’s no time to wash hands, the rest is pointless. Fix the basics first.

🔹 Recordkeeping:

Log your personal hygiene checks — handwashing, cleaning, staff illness, and training. It forms part of your due diligence to protect you if things go wrong.

A Proportionate Supportive Approach To Infection Control

Mary Mallon’s story is as much about ethics as science. In her day, authorities used heavy-handed quarantine and scapegoating. Today, we know that a proportionate, supportive approach works better — screening, treatment, reasonable restrictions and backing staff up when they need it. When your team trusts you, you’ll hear about problems sooner and stop outbreaks before they start.

3 Tips To prevent This Happening In Your Business:

- Blame and shame:

Don’t demonise staff — you’ll drive problems underground. Protect privacy, focus on systems, not individuals. - Complacency:

“We’ve never had a problem” isn’t a plan. Asymptomatic carriage is rare, but it does happen. - Lack of hygiene facilities: If you don’t provide what staff need to keep things clean, don’t expect them to comply with your personal hygiene rules. Read our post to find out what barriers hinder staff in food service businesses from washing their hands.

Next Steps: How to Improve Your Food Safety Controls and Catch a Carrier?

Worried your existing controls wouldn’t catch a healthy carrier of infection in your business?

Book a Clear Path to Compliance call. In one hour we’ll run through a practical system to close all those invisible gaps in your food safety defences.

Get in touch: [email protected] Or call us: 02920 026 566